Child Slavery in Africa from Generation to Generation.

Tuesday, August 11, 2009 at 11:25PM

Tuesday, August 11, 2009 at 11:25PM

The LA Times recently posted an artical byRobyn Dixon about the viscious cycle of slavery in Africa today. One would think that a mother's experience of being a child slave would stop her from selling her own child into slavery, but it does not necessarily.

The LA Times recently posted an artical byRobyn Dixon about the viscious cycle of slavery in Africa today. One would think that a mother's experience of being a child slave would stop her from selling her own child into slavery, but it does not necessarily.

Then there are the parents who are tricked into giving up their child into a slavers hands, only to find out later to their horror what happened. Sometimes this has happened at the hands of a trusted family member.

About 200,000 children in West and Central Africa are slaves, sold by their parents or duped. The children are starved, abused and beaten. But some get their own slaves when they grow up.

says the author in a statement that falls outside the realm of understanding.

By Robyn Dixon

July 12, 2009

Reporting from Kpone, Ghana -- Rebecca Agwu told her 5-year-old son, John, not to cry when she sent him away to live with relatives four years ago. Mary Mootey sent away her 4-year-old son, Evans, telling him he was going off to school. The two boys, now 9, from the same town in Ghana, ended up being forced to work 14 hours a day fishing on Lake Volta and being beaten for the smallest lapse.

Rewind about two decades: Rebecca Agwu was a child herself when her mother sent her away to live with an aunt."I cried," Agwu, 30, recalls. "I didn't want to go, but my mother deceived me that when I went, my aunt would teach me a trade." Instead she was forced to be a domestic worker.

"I never trusted her again. I felt very betrayed."

Evans' mother, when she was 8, was sent by her father to her uncle, a fisherman on Lake Volta, where she was forced to work from 3 a.m. until dark -- cleaning, carting water, cooking and gutting fish.

"My father never loved me when I was young," says Mootey, 35. "I hate him, because he caused all the pain and suffering I went through. I hate him."

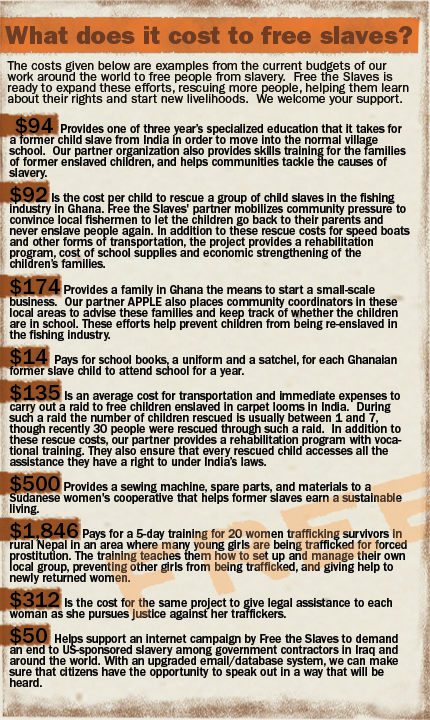

For generations, Ghana and other West African nations have served as a hub for child trafficking and slavery. An estimated 200,000 children in West and Central Africa perform unpaid labor. They are given minimal food and clothing, are deprived of schooling and medical care and are often subjected to physical abuse. Recent laws outlawing slavery in many African countries have had limited effect.

Slavery has a long history in these parts. The Elmina Castle on Ghana's Cape Coast, one of the departure points for the 18th and 19th century slave trade to the Americas, each year draws thousands of African American visitors seeking their roots.

Elmina's dank, black dungeons lead to the "room of no return," with its moldy green walls and oppressive atmosphere. "May humanity never again perpetrate such inhumanity against humanity," reads a plaque at the fortress.

'I was afraid they would kill me'

But today, thousands of Ghanaian children are in unpaid servitude, having been sold for $30 to $50, nongovernmental groups say. Girls are often forced to work as domestic laborers, carting water, fetching wood, sweeping, cleaning, farming, washing, cooking, and in fishing families, cutting up fish and smoking it. They are often sexually abused.

Boys are mostly sent to fish on Lake Volta, where they are taught to swim by being repeatedly thrown off a boat with a rope tied around their waist.

The stories of two mothers and two sons, forced into servitude two decades apart, are equally painful. Agwu's memories of 13 years of domestic labor and beatings are as bitter and sharp as if they had happened yesterday.

"I was afraid all the time. I felt I was nobody. I used to cry myself to sleep."

Though there is so much bleakness, some try to help these children.

Winning freedom through persuasion

On market day, the town of Dambai on the Oti River near Lake Volta is packed with vendors selling smoked fish.

Ragged children sit in small wooden boats, or carry baskets. George Achibra, slave rescuer, points them out.

He doesn't forget a child's face. And when he finds a fisherman unwilling to free his slave children, it only makes Achibra more determined. A former school inspector, Achibra gave up his job in 2006 in Kete Krachi on Lake Volta to rescue children working on the lake. He says he has saved 216 children for various groups, including the Texas-based Touch A Life Foundation and a Ghanaian organization, Pacodep.

"Hundreds of children work on this lake. Their masters don't have the love to take them to hospitals. They don't get enough to eat. Their shelter is poor," he says.

He approaches fishermen and tries to persuade them to free the children and let them attend school. Some get angry and force him to leave, he said. Some move their children to a different place. But sometimes he wins.

His weapons: persuasion and his wide, gleaming smile. "I've never sneaked. All my approach is negotiations," he says.

In a canoe on the shore of the river sits a woman wearing a lime dress and scarf. Near her is a bony child in a red shirt and threadbare shorts. Achibra only has to look at the boy's face to see that he is a slave.

"I'm here to solve your problems," says Achibra, approaching the woman, named Amu Kodor, with a grin. She chuckles at Achibra's jokes. She answers his questions. The boy's name is Francis. The family has four other slave children.

But her eyes dart about uncomfortably when Achibra tells her that the boy must be freed so he can go to school. Francis Tei, 13, stares at Achibra in amazement, his eyes screwed up in the bright sun. But Kodor's face has turned serious. She shakes her head.

When she was a child, she says, her parents sent her away into slavery too, selling clothes.

"It was no good. I had to run away," she says.

When a Times reporter asks why Francis should also suffer, she's silent for a moment. "I have all my children in school," she replies. Only "the master" [her husband] can free the child, she says.

"He's in charge of this boy."

Achibra plans a trip to rescue Francis and the others.

Going through photos of children he has rescued, he points to one skinny child.

"We haven't rescued him yet. But we'll get him."

Fishermen sometimes tell Achibra they hate what he's doing.

Read the rest of the artical here

Contact Robyn Dixon at robyn.dixon@latimes.com

On January 28, Hua Zaichen was rushed to the ER, hovering between life and death. He has been clinging to live in the hope that authorities will allow him to see his wife, Shuang Shuying, one last time. Shuang Shuying, 79, has suffered in prison for almost two years on fabricated charges because of her Christian activities.

On January 28, Hua Zaichen was rushed to the ER, hovering between life and death. He has been clinging to live in the hope that authorities will allow him to see his wife, Shuang Shuying, one last time. Shuang Shuying, 79, has suffered in prison for almost two years on fabricated charges because of her Christian activities.