Tomatoes from the local farmer's market, blanched and ready to peelI am disheartened. I knew about slavery on the Ivory Coast in the cocoa groves, slavery in rice mills, on coffee plantations, domestic slavery. But on tomato farms?

Tomatoes from the local farmer's market, blanched and ready to peelI am disheartened. I knew about slavery on the Ivory Coast in the cocoa groves, slavery in rice mills, on coffee plantations, domestic slavery. But on tomato farms?

I grew up in New Jersey, a state known for its bright-tasting summer grown tomatoes. Families grew tomatoes and sweet corn on their truck farms and sold them at stands on the roadside of the property. Pride would fill the young seller’s face as he or she told you, “Corn was picked in the hour,” thus guaranteeing its sweetness.

Nestled next to the corn, the tomatoes shown in red glory, begging you to slice and salt them, then bite into their juicy goodness. Wholesomeness all the way around.

Then I read the article in WaPo yesterday. When I first saw the header for the continuation of the article, I thought it was a food joke along the lines of tomatoes tasting so wonderful they hold the writer in slavery.

Not the case.

The header was for Jane Black’s synopsis/review of Barry Estabrook’s Tomatoland. Right here on the east coast, four states away, men tricked into slavery harvest tomatoes to sell in the US.

In Jane Black’s own words,

“Lucas Mariano Domingo came to the United States from Guatemala hoping to find a job that would pay him enough to send money home. But he was soon broke and homeless. And so it must have seemed like a lucky break when Cesar Navarrete, leader of a Florida tomato-picking crew, offered him false papers, room, board and a job that, if he did well, could earn him $200 a week.

It quickly became clear, however, that this was a false opportunity. Domingo was lodged with three other men in the back of a box truck with no running water or toilet. Food was scarce. Navarrete charged extortionate fees for just about everything. After a hot day in the fields, Domingo was docked $5 to stand naked in the back yard and wash himself with cold water from a garden hose. He was paid irregularly and in small, arbitrary amounts. Worse, Navarrete warned that Domingo or any other laborer who attempted to leave would be severely beaten. It took Domingo nearly three years to escape — and even longer before members of the Navarrete family were charged with what Douglas Molloy, the chief assistant U.S. attorney in Fort Myers, Fla., described as “slavery, plain and simple.”

In the 21st century, such horror stories should be uncommon. But over the past 15 years, Florida law enforcement officers have freed more than 1,000 men and women who were held against their will and forced to work in the fields.”

Read the rest here:<a href="http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/books/barry-estabrooks-tomatoland-an-indictment-of-modern-agriculture/2011/04/11/AGei5rOH_story.html"> Barry Estabrook’s ‘Tomatoland,’ an indictment of modern agriculture </a>

Monday, March 11, 2013 at 01:33PM

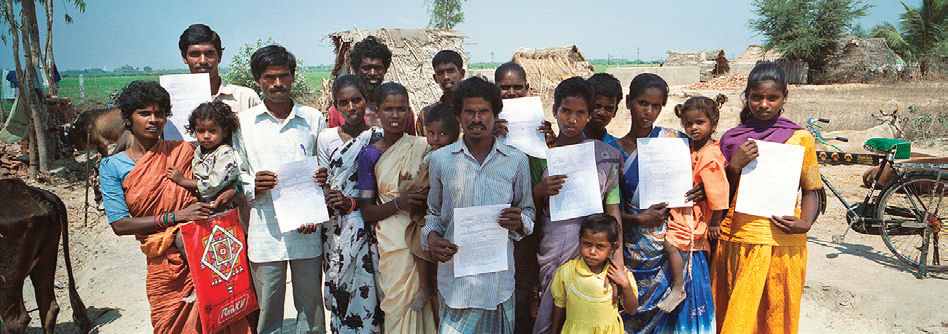

Monday, March 11, 2013 at 01:33PM  about the kiln. Together they worked with the district government and local police to free those enslaved inside the factory. They entered after nightfall and found people still working. A pregnant woman had been kicked when she begged for rest. A man had been beaten so severely, his bones showed through still bleeding wounds. Sunken cheeks and bellies attested to the lack of food supplied to the slaves. The kiln owners would not even allow them a full night’s sleep.

about the kiln. Together they worked with the district government and local police to free those enslaved inside the factory. They entered after nightfall and found people still working. A pregnant woman had been kicked when she begged for rest. A man had been beaten so severely, his bones showed through still bleeding wounds. Sunken cheeks and bellies attested to the lack of food supplied to the slaves. The kiln owners would not even allow them a full night’s sleep.